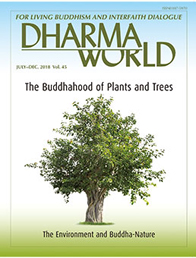

July-December 2018, Volume 45(PDF)

The Buddhahood of Plants and Trees: The Environment and Buddha-Nature

In Buddhism the idea that “All sentient beings possess buddha-nature” first appeared in the Mahayana Nirvana Sutra, which was translated into Chinese in the fifth century, and exerted a great influence upon Buddhism in China and Japan.

In Japan, the Tendai monk Annen (841–915?) asserted that even non-sentient beings, to say nothing of sentient beings, possess buddha-nature and can even attain buddhahood. This idea was widely accepted in Japanese Buddhist circles and also left its mark on literature and the traditional arts, such as Noh drama.

The idea that spirits dwell in plants and all objects that comprise the natural environment is common to Shinto and is familiar to many Japanese people. It is also often referred to in the discussion of environmental protection as an important concept informing Japanese views of nature, and may underlay the idea of harmonious coexistence between human beings and nature which is popular in Japan.

The buddhahood of non-sentient beings means not only that plants and all aspects of the environment possess the buddha-nature, but also that they can attain buddhahood. This prompts us to imagine dynamic relationships, if not visible interactions, between human beings and plants, and between human beings and all things that make up the natural environment, as fellow beings that possess the buddha-nature and the potential to attain buddhahood.

The global climate is changing rapidly largely due to the exponential increase of humanity’s economic activities, which affect the subtle balance of biological ecosystems and put the survival of many species at risk. At such a time, it may be useful to reconsider the idea of the buddhahood of non-sentient beings as part of our quest for a way in which human beings and all things in nature can live harmoniously, which may be our only option if future generations of humanity are to survive on planet Earth.