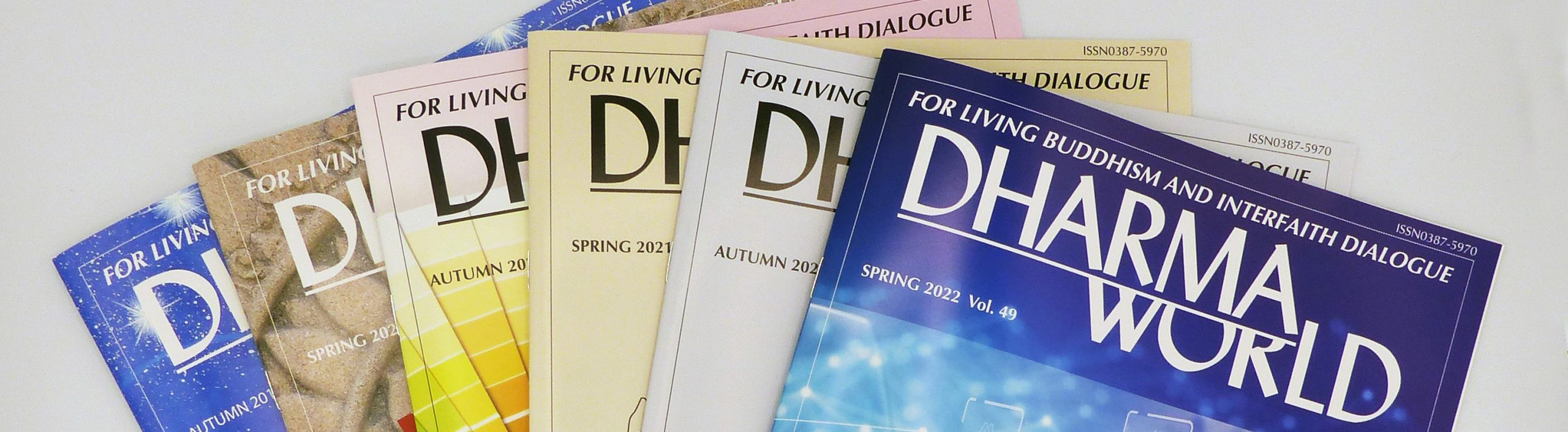

October-December 2015, Volume 42(PDF)

The Modern Significance of Meditative Practices in Religions

Meditative practices are entering the mainstream of societies in many parts of the world. These practices are not necessarily tied to religions, but as Time magazine observed of “mindfulness meditation” in its February 3, 2014, issue, meditation is becoming popular as a neurophysiological approach to mental stress in hectic contemporary societies, and is even used as a complementary treatment for physical pain.

Meditation, or voluntary self-regulation practices to develop fully focused awareness or gnosis, has been an important component of many religious traditions. Zen Buddhists, for example, hold that zazen is an essential practice on the path to enlightenment, or liberation from suffering.

The aims and forms of meditative practices vary according to different religions, however, and there is also significant diversity within single religious traditions. The meaning of meditation in each religious tradition is also framed by different belief systems. This makes it hard to grasp the significance and meaning of meditative practices in religious traditions other than one’s own.

While meditative practices are drawing attention as forms of mental or physiological fitness, examining their current religious significance would promote understanding of meditative practices as an important aspect of religious training, and not only as methods of stress reduction. Our examination would shed new light on this ancient religious heritage, and we hope meditation will become a more ample religious resource for happier and healthier lifestyles of people today.

To gain an overview of what significance meditation has in religions today, we would like to approach the theme from the following angles: (1) What are the various forms of meditative practices, and are they associated with different effects or mental and physiological benefits? (2) Why have meditation practices (e.g., mindfulness meditation, yoga, etc.) gained mainstream popularity as ostensibly “secular” practices? (3) Can these practices be separated from their religious contexts, and if so, what are the consequences? (4) What does the popularity of meditation practices signal about contemporary culture and the needs of people in advanced technological societies? (5) Are religious meditative practices crossing sectarian lines? Have they become the basis for, or facilitated, intersectarian and interreligious cooperation and understanding? (6) Are meditative practices as medically effective as their advocates claim?